Memorization vs. generalization in deep learning: implicit biases, benign overfitting, and more

Or: how I learned to stop worrying and love the memorization

Is there a fundamental tradeoff between memorization and generalization, or is their relationship more nuanced? Questions like these come up again and again in machine learning, most recently in discussions about language models — are they just a “blurry JPEG of the web” as Ted Chiang wrote? I’ve felt like there isn’t a good high-level overview of the nuanced relationship between memorization and generalization as we understand it in the theory and practice of machine learning today. Thus, today I want to write a bit about how I think the field’s understanding of these issues has evolved over the past few decades.

Classical perspectives:

In classical learning theory, there is a fundamental tradeoff between memorization capacity and generalization — models that are able to memorize arbitrary data should not be expected to generalize. This notion is captured in the VC dimension bounds on generalization error, which (very loosely) says that models that can memorize a relatively small amount of the training dataset will have test error close to the train error, while models which can memorize the training data can have arbitrarily bad test error.

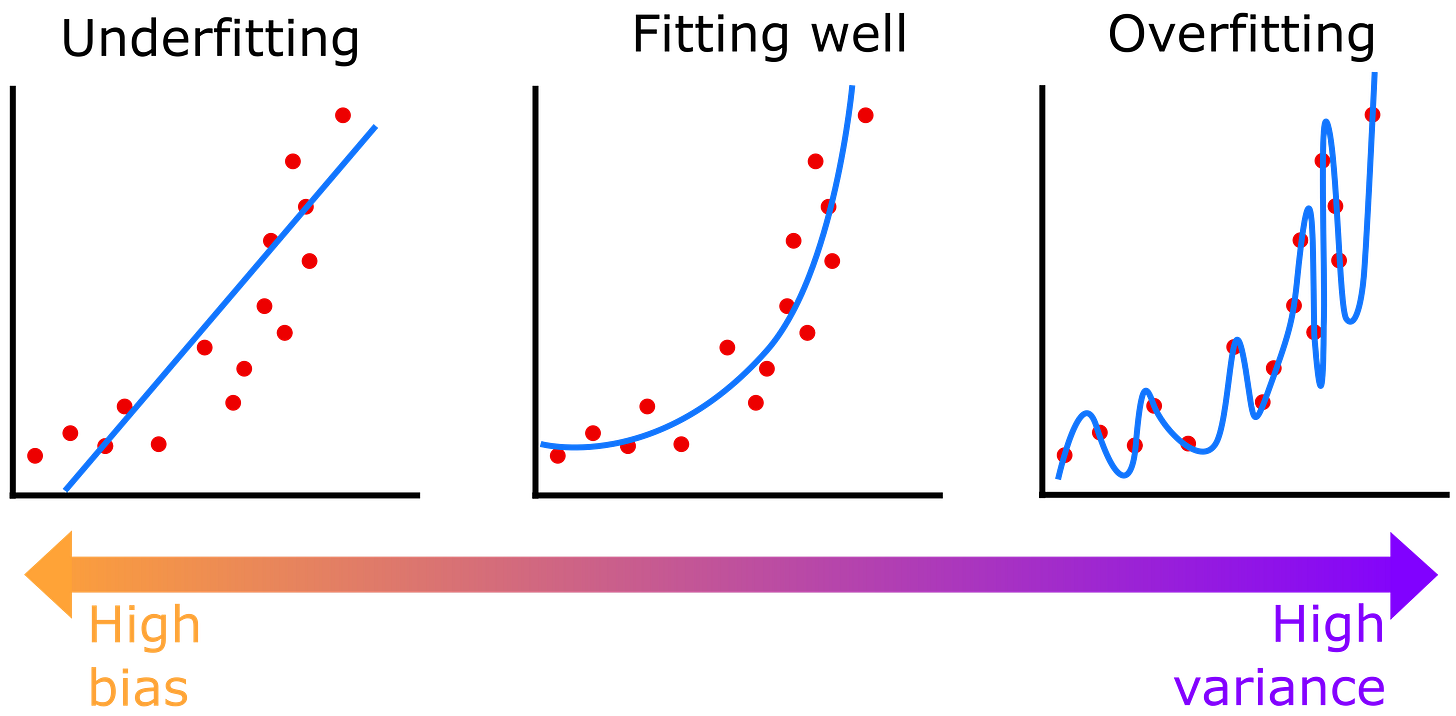

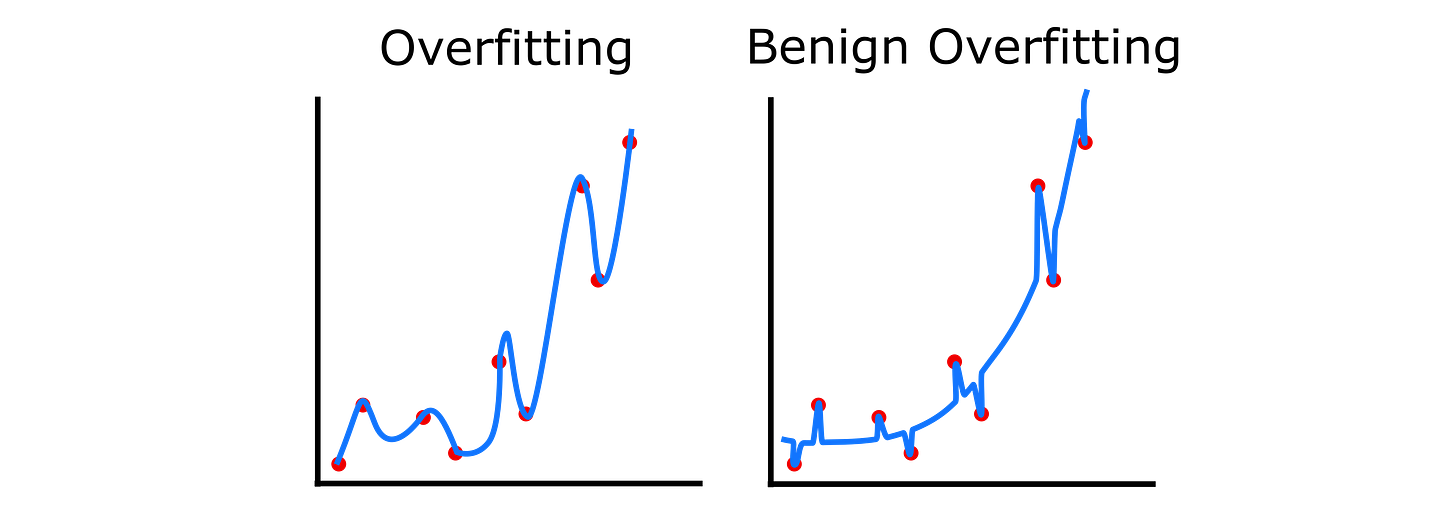

This makes intuitive sense if you think of a picture of what it means to overfit a polynomial to some points:

Being able to memorize all the data points means the function is much too complex, and that it will therefore make much worse predictions about new data points than a function that can only memorize a few data points. This can be seen as an instance of Occam’s razor; it’s better to favor simple explanations. The simplest polynomial that can get reasonably close to all the data will probably give the best predictions; a complicated one that matches everything perfectly will probably do worse. (The VC dimension bounds are about classification, not regression, but the intuition for why memorization capacity might make a model worse is similar.)

A memorization puzzle:

Over a decade ago, deep learning models for vision started to dominate competitions like ImageNet, achieving high accuracy, and even learning features that generalized well to entirely new tasks. However, in a paper first released 10 years ago, Chiyuan Zhang and colleagues pointed out a puzzle these empirical results pose for the classic story above. Specifically, the authors showed that these successful deep learning models were capable of memorizing entirely random labels for the ImageNet datasets — even when applying regularization. Yet, despite this capacity for memorization, the models generalize well!

Clearly, the simplest version of the picture above can’t be true; there must be something that pushes deep learning models away from purely overfitting even in cases where they could. (N.B.: this doesn’t contradict the generalization bounds given by VC theory; it just shows that they are looser than they could be.)

In search of implicit simplicity biases:

The observations above led researchers to search for some implicit bias towards learning simpler functions1 — rather than complex squiggly ones like the overfit example above. This bias must be implicit in the sense that it was not intentionally created by the model designers, but rather something that happens to be true of the models or optimization processes more generally. Indeed, researchers have since proposed a number of such implicit biases that might explain the generalization we observe in practice.

One plausible source of bias is architectural; that something about neural networks is inherently biased towards simpler functions. There is some evidence for this. A particularly nice example of this comes from a paper by Valle Pérez & collaborators that shows both theoretically and empirically that randomly sampled parameters will be exponentially more likely to instantiate a simpler function than a more complex one. Thus, if we imagine that the model is randomly sampling from among the possible solutions to the problem that it can implement, it will tend to hit simpler ones much more often, which may help it to generalize. Other papers have studied many other architectural features that improve generalization, e.g., why deeper models may be more biased towards simpler solutions.

However, some of the arguments above — and many more relatively architecture-independent ones — depend on the optimization process, which I will turn to next.

Optimization biases — simpler functions are learned first:

One of the most commonly-studied sources of bias is the optimization process itself — with the idea that what is learned first will tend to be simpler. For example several papers show that models trained with gradient-based optimization tend to learn linear structures in the data before (or in lieu of) learning nonlinear structures — and these simplicity biases persist in their representations even when the more complex nonlinear features have been learned later. Humans also show similar simplicity biases in terms of how quickly they learn different types of concepts. The ease of learning may favor simplicity, which in turn may encourage generalization.

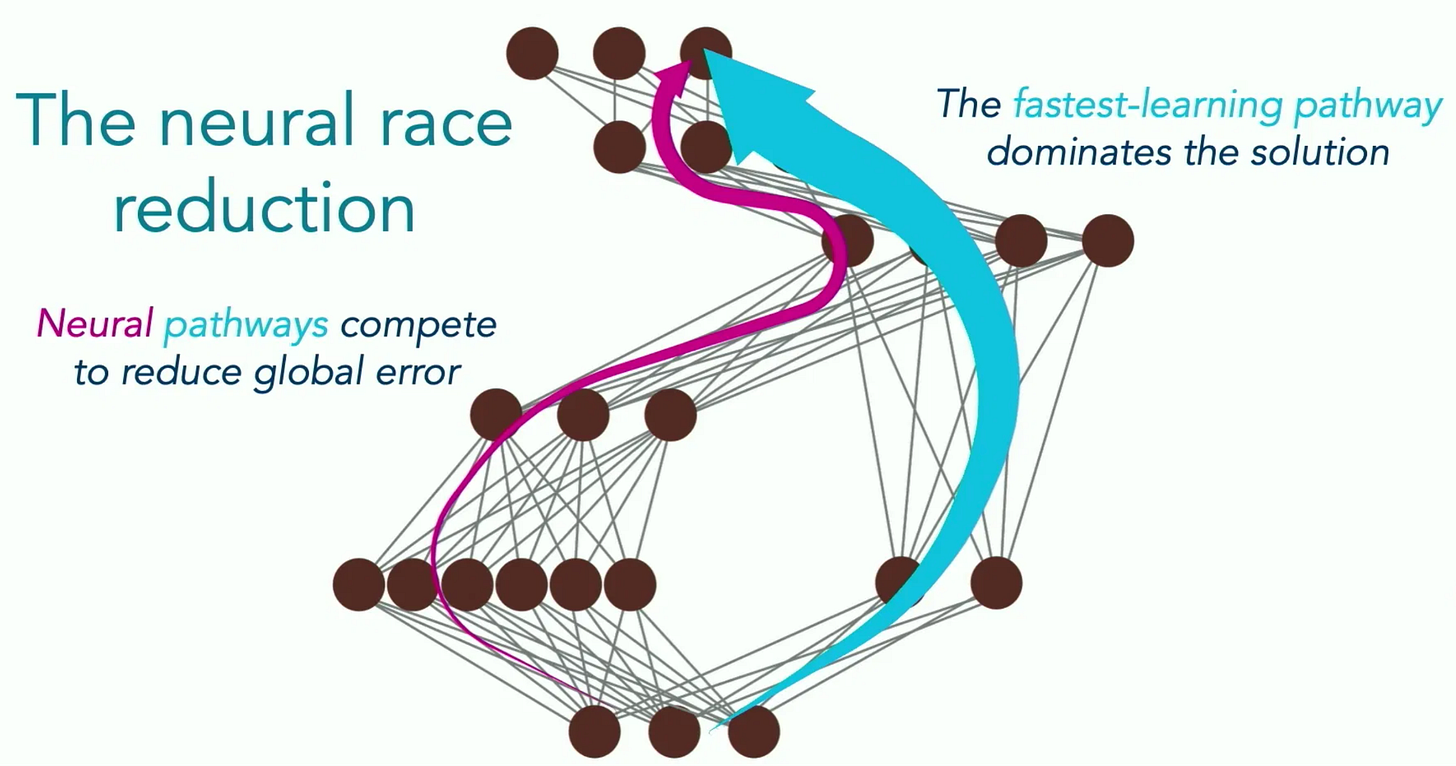

Another optimization-based perspective I find particularly useful is The Neural Race Reduction by Saxe & Sodhani. The authors demonstrate through both theory and empirics the idea that if a model has multiple ways to solve a problem, the one that leads to the fastest learning will tend to dominate. For example, solutions that share more structure across multiple tasks will tend to be learned faster than solutions that are idiosyncratic. Intuitively, these will tend to be the solutions that generalize, rather than those that memorize individual facts. In fact, it is precisely because the solutions generalize that they are learned faster; the fact that they apply to more instances means they get more frequent and more consistent gradient updates than idiosyncratic solution paths do.

This result resonates with an earlier study in which we showed analytically in much simpler settings (deep linear networks learning linear functions) why learning a signal shared across many data points will be faster than memorizing many individual random labels; the memorizing case spreads the same total signal out over many different modes, each of which is learned more slowly. Likewise, signals that are shared across multiple tasks will tend to be learned faster and more reliably than signals that are not shared.

There are many more recent papers that extend, elaborate, or add nuance to this perspective, but I think the overall intuitions here — that simpler, shared structures will tend to dominate because they contribute to solving more problems — are a good starting place for understanding why optimization processes may bias models towards common, generalizing structures.2

Memorization is not incompatible with generalization

In practice, however, deep learning models do memorize some of their training data. Does this hurt generalization? In some cases, it may not!

First, there may be cases where models memorize in a way that doesn’t hurt generalization (but also doesn’t help it), which is often referred to as benign overfitting. This has been demonstrated empirically and theoretically in various settings, from linear to nonlinear models. The intuitive picture is that models learn both the common structure in the data and memorize the idiosyncrasies, but when a new data point is not too close to a memorized example, they will tend to fall back to the simple, generalizing structure. Thus, memorization may not be as bad as it is often assumed to be — while overfitting distorts the global structure, benign overfitting causes distortions only locally.

More surprisingly, however, in some cases memorization may actually help models to generalize. In particular, several papers have argued that memorization may be needed if there are some obscure structures in the data — either rare exceptions that are unlike the other examples (e.g., a penguin is unlike other birds in numerous ways), or actual errors in the data (e.g., because real datasets often have some percentage of wrong or incomplete labels). If the model tried to learn these rare examples with the same structure as the other examples, it might hurt generalization. In this case, memorizing exceptions or rare examples actually protects the simpler, generalizing structures on the rest of the data.

There are also some reasons to think that early in learning memorization itself might help to more effectively set up the representations for learning shared structures; we’ve observed several instances in recent papers where having common “celebrity” entities that are often encountered, or even explicitly repeated data, can accelerate learning of mechanisms (e.g., sparse attention patterns) needed to support instances beyond these. Thus, memorizing can support later learning and generalization.

Several recent theoretical works have elaborated and deepened these stories — highlighting how (at least for some problems) memorization of some training data may be necessary for effective generalization, including memorizing information irrelevant to the target task, and how trading off learning shared structures and memorizing unpredictable ones can lead to optimal generalization. In a recent preprint, we’ve also argued that explicit episodic recall may be needed to unlock certain types of generalization to tasks sufficiently different from the training — that is, memorizing veridical experiences (in a complementary episodic storage system) may be necessary for reusing information flexibly, because the abstractions induced by task-oriented learning inherently discard information that might be useful for sufficiently different future tasks.

Thus, while we do not understand the complete picture of memorization and generalization across all problems, there are a number of lines of evidence suggesting memorization is not always detrimental to learning generalizable structures, and may in fact support some types generalization.

There are also traditions of memorization in human education, even when there is an underlying principle from which the memorized instances can be inferred, e.g., memorizing multiplication tables as a part of learning mathematics. It is interesting to speculate about whether these practices help with learning underlying principles per se (or whether they help performance through more prosaic mechanisms, e.g., having cached solutions to subproblems that reduce working memory load).

What does this all mean for language models?

Nowadays, there are many discussions in the academic literature, popular press, and social media about the extent to which language models can generalize. Often, critical perspectives lean on metaphors about (approximate) memorization — language models are “just” stochastic parrots or blurry JPEGs that partially regurgitate their training data in response to new prompts. These perspectives are buttressed by clear observations that language models do memorize some of their training data in a way that increase with scale, and more concerningly, that proximity to training data drives some of their performance. For example, when researchers create items that are similar to a familiar brainteaser, but that change the logical structure to be much simpler, models often incorrectly respond with a memorized answer pattern (example from twitter, paper) — a clear instance of overfitting. Findings like this, as well as patterns such as models performing better on more frequent items have led researchers to argue that these models are not truly reasoning or generalizing.

However, I hope that the examples above show why we might hope that models will learn to generalize rather than, or at least in addition to, simply performing lossy memorization. For example, even if models overfit on instances resembling well-known brainteasers, this overfitting could be “benign”, in the sense that it doesn’t harm generalization much outside the neighborhood of similar-sounding problems (though of course, we would like models to generalize on these instances, too). Indeed, benign-overfitting-like phenomena have been documented in language models in controlled studies, such as strong generalization even after memorizing noisy parts of data, larger models memorizing more without overfitting, and models learning organized representations that capture generalizable structure in the data, rather than simply memorizing associations.

These findings on memorization complement a broader range of studies showing how language models can learn generalizable syntax or algorithms in controlled settings where what is held out is known, and data-influence-based studies suggesting that memorization is not the key driver of performance on reasoning problems; instead, models infer generalizable procedures. We have strong empirical reasons to think that language models learn generalizable abilities from their training — and some theoretical intuitions of why that might happen — even when they memorize nontrivial quantities of training data, and even if they do not always generalize in the ways that we would hope.

Of course, none of this precludes the possibility that there are strategies for encouraging models to generalize better. There’s a lot more to be said on retrieval, RL vs. imitation, modern reasoning-trained models, etc. of course — stay tuned.

There’s an implicit assumption in the arguments here that simpler functions = better generalization, but of course there are cases where this isn’t true, as a nice paper by Harshay Shah and collaborators shows. Indeed, in more complex settings, it is not even always trivial to define what is simpler; it can have complex interactions with architecture and training objective (see e.g. this paper).

There have also been a number of papers that try to adapt generalization theories to account for implicit biases like those discussed, e.g. by measuring the “capacity” of a model in terms of parameters that measure how much it has actually learned from the data, via measurements like parameter norms or compressibility. These are potentially promising approaches for reconciling theory with the empirics of deep learning — though so far, it’s not obvious to me if they have successfully done so. E.g., as a recent compression-based paper notes in its limitations, their bounds still favor models with fewer parameters, when in practice larger models generalize better. Nevertheless, I think that these approaches are promising directions for further investigation.