What cognitive science can learn from AI

#3 in a series on cognitive science and AI

I get asked a lot of questions about the relationship between AI & Cognitive Science, especially from early-career researchers wondering where their work might fit into the rapidly evolving fields. This is the third in a series of posts where I aim to lay out my current thoughts on the relationship between these fields — and the career options in them — in the present research environment. Everything here is my personal opinion; almost any claim I make some researchers would stridently disagree with. So take it with a grain of salt.

In the past two posts, I’ve laid out where I think cognitive science can and can’t be useful for AI. Here, I want to look the other direction, and talk about lessons that I think cognitive (neuro)science can learn from AI. This post will largely follow a preprint that Wilka Carvalho and I wrote arguing for a similar perspective, though here I’ll give a more succinct argument with a slightly different focus.

What should cognitive science learn from AI?

At a high level, I think that cognitive science can learn from AI that:

Scale and richness of learning experiences can fundamentally change learning & generalization.

Thus, the solutions to toy problems are not necessarily the best solutions for problems at scale — especially if the toy problems are constructed to demonstrate one’s pet theory (be careful of “setting your own homework”).

And the computational solutions to tasks individually may be quite different from the solution that solves them all relatively well.

Natural intelligence operates in the regime of learning at scale, and solving many tasks. But most cognitive models focus on solving an extremely narrow task — a single, simple experimental paradigm. This mismatch can limit our ability to achieve understanding. As I said in the first post of this series, an adaptive system can be like a mirror — if you’re not careful, the system just reflects the structure in which you test it.

Thus, in order to understand such a system, it’s important to understand how it adapts across a broader range of tasks.

Richness & scale of experiences change learning & generalization

The first point I want to make is that when the scale and richness of learning experiences are enhanced, they tend to enhance what is learned and how the system generalizes. For example, when a system learns in a broader set of situations (scale) and those situations have more of the perceptual or motor complexity of the real world (richness), what it learns is fundamentally different than what a model will learn in a toy setting. At some level, this point is intuitive, and relates to well-established phenomena in cognitive science (and in literature, as with the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea demonstrating the power of multi-sensory memory). But, the last 10 years of progress in AI have been strongly driven by this lesson.

Because there can be many confounds introduced in uncontrolled comparisons of scale and richness of learning, I’ll illustrate my points with a few examples from controlled experiments in AI. (See also a recent commentary where I discuss these issues.)

In a recent study, Misra & Mahowald studied how language models generalize to a particular linguistic structure, in cases when it never appears in training. They found that the models generalize from related constructions (e.g. components of the novel construction) that they have encountered in training. Crucially, they found that this generalization was enhanced by the variability in the semantic fillers observed in these structures during training. This shows how real, structural generalization can be enhanced by richer data.

In a study of causal reasoning & generalization, we similarly showed that the ability of an agent to generalize causal reasoning strategies to novel causal dependencies (never observed in training) depended crucially on the variability of the causal structures that had been observed in training. We also showed that features that enriched the learning with other cues, such as natural-language explanations, could enhance that generalization (as we’ve also found in prior work).

In a study led by Felix Hill, we showed how compositional generalization of language can be fundamentally altered by the richness of the environment in which it is learned. We took the same compositional train-test split of language, and experimented with how generalization was affected by the setting in which models learned the language. We found that agents that learned language grounded in an interactive, 3D environment generalized much more effectively (100% accuracy) than agents that learned simply from images, and likewise agents trained in 3D generalized better than those trained in 2D. This shows how richer features like embodiment might affect structural generalization. (I’m disappointed to say that I’ve seen little evidence from controlled experiments that grounding or embodiment per se improve language models when evaluated in language alone… though perhaps it’s yet to come.)

Raventós & Paul show that, when training a transformer model model on an in-context linear regression task, there is a phase transition in generalization as the diversity of training tasks increases. Before this transition, the model essentially behaves with a memorization-like prior (a mixture of tasks seen in training); after the transition, however, it closely approximates the true prior over all tasks, including unseen ones.

These examples show how having a greater scale of examples to learn from, and richer features in those examples, can change what a system learns, and enhance its generalization. And there are many examples of how features like scale (e.g. of number of exemplars) and richness (e.g. of backgrounds behind objects) can enhance learning and generalization for natural intelligences like humans.

Systems that solve many problems are different from those that solve individual problems

I believe that the observations above are behind a fundamental shift in the way we approach solving problems in machine learning. In some sense, AI is now doing a much better job of solving general classes of problems like answering arbitrary questions in natural language, or identifying the objects in natural scenes, than prior systems did at solving much narrower problems like coreference resolution or classifying individual categories. Indeed, state-of-the-art methods for solving narrow linguistic problems now involve taking a general pretrained model, and adapting it to the specific tasks — just like state-of-the-art methods in computer vision for the last ten years have involved starting from models trained on large datasets, and ever more general tasks. We’ve moved from hand-engineering solutions to particular problems, to largely relying on general learning at scale, with a bit of task-specific learning at the end.

Why is it easier to solve a much more general problem — make a system good at many things, and then specialize it for some particular task — than it is to solve a narrow, specific problem? I’d argue that it’s due to precisely the type of pattern I’ve highlighted above: that systems that learn from a larger scale of richer data learn fundamentally different (and better) features and inferential processes than those that are trained in simpler, smaller-scale settings.

Toy problems, and setting your own homework

In the first post of this series, I mentioned that minimalistic task design is often a design principle of cognitive (neuro)science, but one that also might be holding the field back, by focusing our understanding of systems onto narrow settings. I think that the discussion above offers a different perspective on these issues: if richer and larger-scale settings can fundamentally change what a system learns and how it generalizes, than studying learning & generalization solely in toy settings may mislead us.

A particularly insidious case of this is when a toy problem builds in precisely the structure the researcher is looking to find in the natural system (which Daan Wierstra once described to me as “setting your own homework”). For example, if a researcher believes that the mind does something like “logical inference,” they will naturally design a minimal, toy task that is fundamentally structured as a logic problem, then show that their system does well (perhaps better than a neural network). Of course, where humans also perform similarly, this is suggestive of an interesting capability to mimic such a system in some capacity. However, as highlighted above, the solution to many problems may be different from the solutions to individual ones. And this is particularly problematic when most of the problems that humans solve do not as obviously have the clear structure (e.g., logic) that the toy problem does. Of course your logic system works well on logic problems, but how does the human mind know when to use strict logical inference and when to use other processes? And does it really do strict logical inference, or might it be something not so different from what language models do? Knowing what a system does in a limiting case gives us only a very narrow window into how it works.

For this reason, Wilka & I recommend that researchers separate the creation of benchmarks that define a problem from the proposal of solutions, and keep one fixed when changing the other. We think that toy problems are a useful starting point for investigations, but we also think that it is important that candidate models of cognitive phenomena can be scaled to solve many problems, to show that the solutions can scale and what that scaled implementation might look like.

(I don’t want to be overly critical of others here; I think that this is something I have done a poor job of at many times in my career — I have too often designed test settings alongside the algorithm that I believed would solve them, without demonstrating that the solution can scale — and this is something that I aim to do better in present and future work. I do think there are things to be learned from these works, but I think they are less general than I hoped they would be.)

In the last sections of our paper, Wilka & I propose an approach to building theories in cognitive science that I think addresses these challenges.

Building naturalistic paradigms without giving up experimental control

We argue that cognitive science needs to build towards more complex, naturalistic experimental paradigms that can capture the broader range of variables and situations across which a theory would be expected to hold. While the idea of naturalism is often pitted against the possibility of experimental control, we argue that it is possible to do theory-driven experimental manipulations in naturalistic experiments — maintaining control of the variables of theoretical import, while varying the many others that may interact with them to ensure that the effects we discover are general.

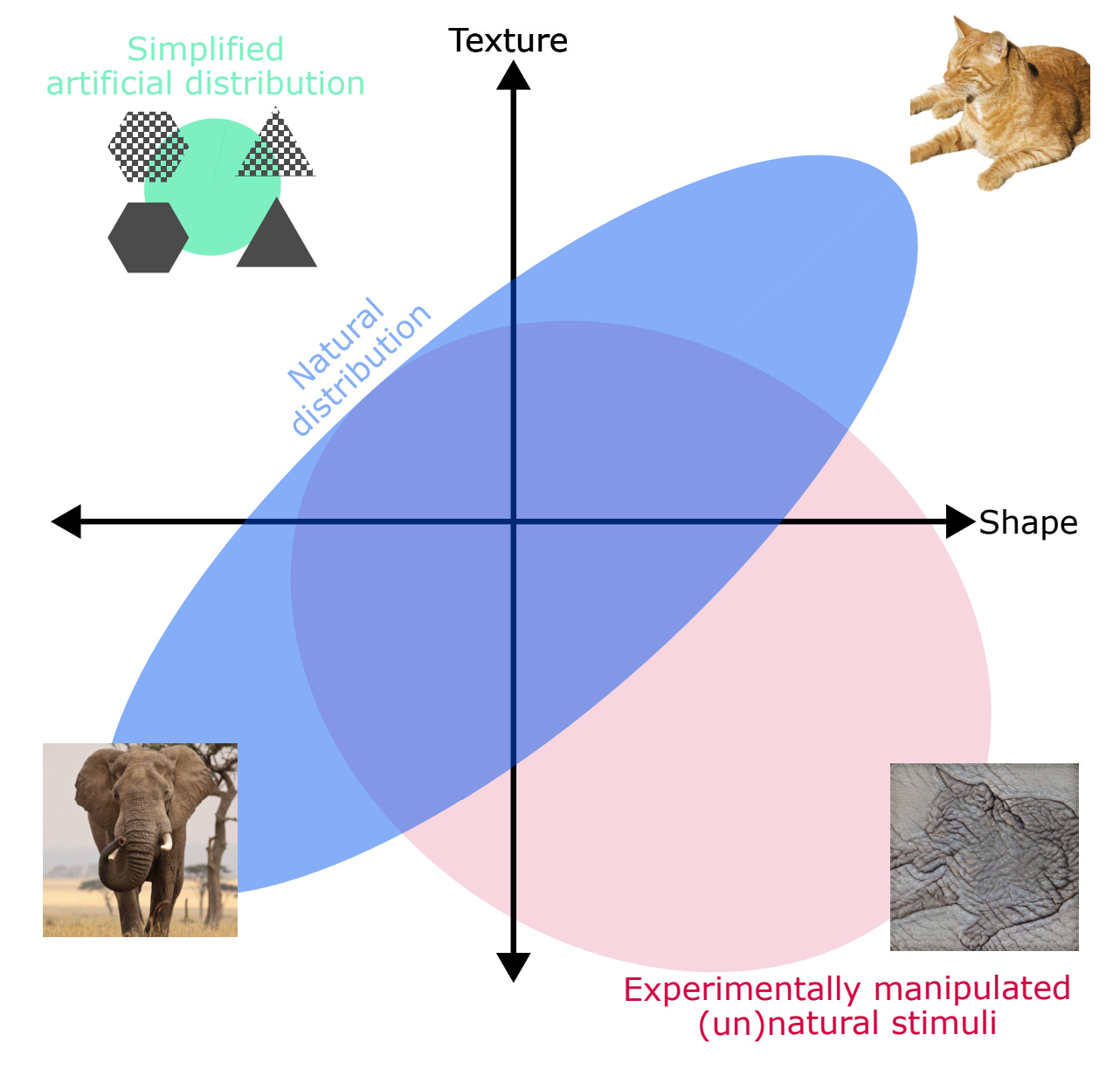

For example, using machine learning tools, programmatic methods, and/or human effort, it is possible to take a widely varying set of natural stimuli, and augment them to capture the effects of interest — even in unnatural ways that go far outside the natural distribution, as when Robert Geirhos and colleagues artificially constructed stimuli with the shape of one object, but the texture of another (though cf. this more recent paper).

Other researchers have done similar experimental manipulations like augmenting real stories with unnatural grammatical structures, or sampling variations of maps for a videogame environment that systematically vary particular features — showing how data with rich natural structure can be enhanced with systematic manipulation of key variables.

But how can we tightly link these naturalistic experiments to our models and theories?

Building theories that combine naturalistic task-performing models with reductive understanding

There is a tension between building large-scale task-performing models, and building understanding as cognitive scientists. Our resolution of that tension is that cognitive scientists need to do both, and link them more closely than they usually are.

We think that simple models on toy problems (or other methods of reductive understanding, such as analytic theory) are one essential piece of cognitive theories, but not the whole of it. Instead, we argue that these simpler components need to be grounded in models that can really perform the same range of naturalistic tasks as the natural intelligences do, in as similar a range of naturalistic settings as possible.

The reductive component of such a theory helps us to achieve the abstract understanding that cognitive scientists seek. But crucially, tightly coupling these theories to models that can really perform the tasks in question allows us to see that the solutions are scalable, and can address the full range of behaviors, rather than simply those that match the theory exactly.

Importantly, we are increasingly getting the tools that allow us to make these links between simple and scaled-up models precise. One particularly promising example is Distributed Alignment Search by Atticus Geiger & Zhengxuan Wu (and others), which allows making precise causal links between simple, structured causal models and the distributed representations learned in large machine learning models. But these interpretability-based methods are not the only route. There are also many other paths to achieving reductive understanding, such as theories of deep learning that elucidate cognitive phenomena (for example, in semantic cognition), that can still tightly link to the task performing models.

Summary

I think that cognitive science can learn from AI about the importance of scale and richness of learning experiences in generalization. That should make us concerned about overly narrow experimental paradigms and models, and push us to build more naturalistic ones. Even in naturalistic settings, we can maintain experimental control. And we should aim to build theories that tightly couple reductive, abstract models to ones that really perform the naturalistic tasks that the natural intelligences do.

For a much deeper discussion of these topics, and the challenges and limitations therein, and the prior literature, check out our preprint (and keep an eye out for a new & improved version, hopefully sometime soon).

One thing AI has clarified is that generalization emerges from recursive compression across many environments, not from solving isolated paradigms cleanly. Toy tasks often capture a slice of behavior but miss the dynamics that determine when and how a system updates its representations. That gap seems central to the limits of many cognitive theories.